The Great London:

Greece

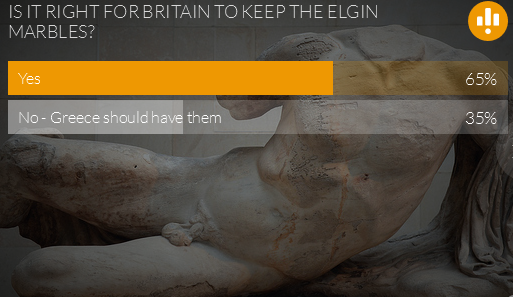

United Kingdom: Britain urged to begin talks on Parthenon marbles

United Kingdom: Athenians’ association sues Britain for Parthenon Sculptures

More Stuff: Is Greece about to lose the Parthenon Sculptures forever?

More Stuff: Telegraph: Greece has no legal claim to the Elgin Marbles

United Kingdom: Greece will not go to court over Marbles, says minister

United Kingdom: Greece looks to international justice to regain Parthenon marbles from UK

United Kingdom: British pensioner 'finds' 2,300 year old ancient Greek gold crown in box under his bed

United Kingdom: So-called 'radical left' gov’t of Greece will not legally pursue return of Parthenon sculptures

Great Legacy: The Salonika Campaign: archaeology in the trenches

United Kingdom: First-ever legal bid for return of Parthenon Sculptures to Greece thrown out by European Court of Human Rights

Greece: Did ebola strike Athens in 430 BC?

United Kingdom: British MPs introduce Bill to return Parthenon Sculptures to Greece

More Stuff: 'A dream among splendid ruins...' at the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

United Kingdom: Britain has kept the ‘Elgin Marbles’ for 200 years – now it's time to pass them on

Turkey: Early farmers from across Europe were direct descendants of Aegeans