The Great London:

Human Evolution

Human Evolution: Monkeys are seen making stone flakes so humans are 'not unique' after all

Genetics: Obesity in humans linked to fat gene in prehistoric apes

Evolution: Study sheds light on the function of the penis bone in male competition

Genetics: Genes for nose shape found

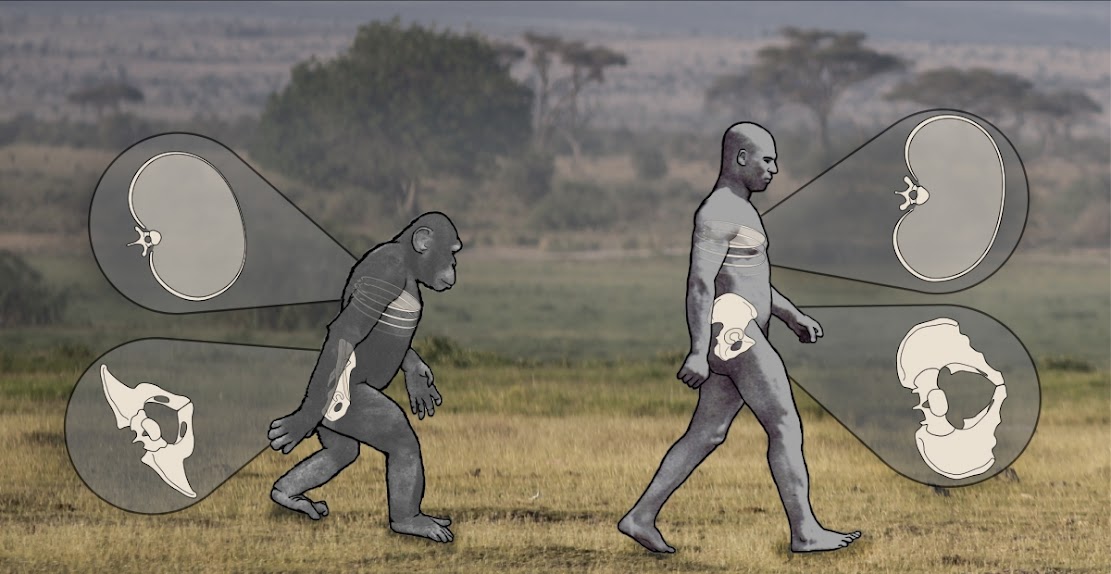

Genetics: Tweak in gene expression may have helped humans walk upright

Fossils: Ear ossicles of modern humans and Neanderthals: Different shape, similar function

Philippines: What Hunter-Gatherers can tell us about fundamental human social networks

East Asia: How China is rewriting the book on human origins

Human Evolution: DNA from Neanderthal relative may shake up human family tree