The Great London [Search results for Dinosaurs]

Fossils: Stegosaurus bite strength revealed

Mongolia: First demonstration of sexual selection in dinosaurs identified

Fossils: Long-necked dino species discovered in Australia

Fossils: Scientists explain evolution of some of the largest dinosaurs

Fossils: Mammal diversity exploded immediately after dinosaur extinction

Fossils: Mammals evolved faster after dinosaur extinction

Italy: Fossil find reveals just how big carnivorous dinosaur may have grown

Fossils: Dinosaur fossil investigation unlocks possible soft tissue treasure trove

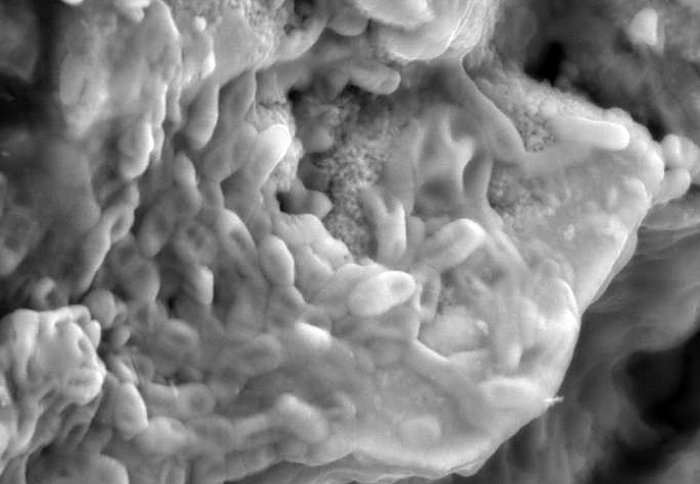

Palaeontology: Fossilized dinosaur brain tissue identified for the first time

Dinosaurs: Scientists carry out 'autopsy' on life-sized T-Rex replica

Mexico: Expedition will sample crater left by dinosaur-killing asteroid

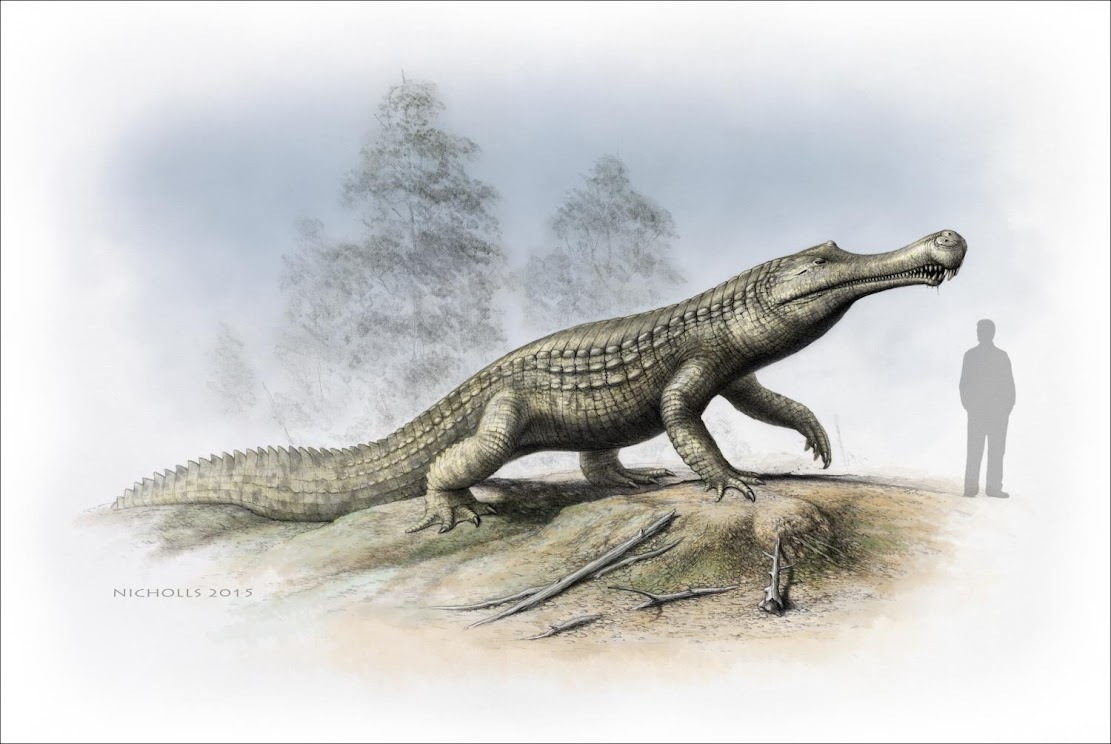

Fossils: Cold snap: Climate cooling and sea-level changes caused crocodilian retreat

Palaeontology: Newly discovered pliosaur terrorised ancient Russian seas

Mauritius: Dodos might have been quite intelligent, new research finds

Mexico: Asteroid impacts could create niches for early life, suggests Chicxulub crater study

Japan: Unique Mosasaur fossil discovered in Japan

Fossils: Oldest pine fossils reveal fiery past

Genetics: A 100-million-year partnership on the brink of extinction

Fossils: Decline of crocodile ancestors was good news for early marine turtles

Natural Heritage: Fate of turtles, tortoises affected more by habitat than temperature