The Great London [Search results for Earth Science]

Earth Science: Cosmic dust reveals Earth's ancient atmosphere

Astronomy: Evidence of Martian life could be hard to find in some meteorite blast sites

Breaking News: Titan's atmosphere even more Earth-like than previously thought

Geology: Common magnetic mineral is reliable witness to Earth's history

Earth Science: Researchers explain why the Greenwich Prime Meridian moved

Mexico: Asteroid impacts could create niches for early life, suggests Chicxulub crater study

Astronomy: Strong ‘electric wind’ strips planets of oceans and atmospheres

Space Exploration: Scientists identify mineral that destroys organic compounds, with implications for Mars Curiosity Mission

Breaking News: Solar storms trigger Jupiter's 'Northern Lights'

Astronomy: Fossilized rivers suggest warm, wet ancient Mars

Environment: Not so crowded house? New findings on global species richness

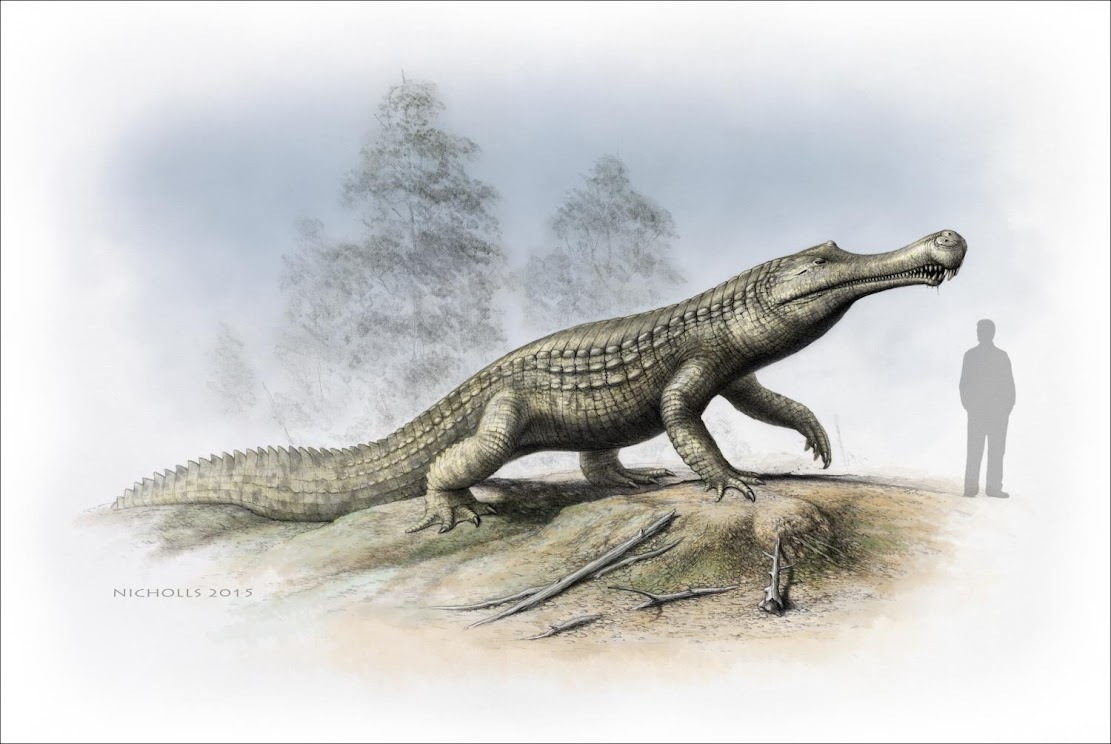

Fossils: Cold snap: Climate cooling and sea-level changes caused crocodilian retreat

Oceans: First evidence of deep-sea animals ingesting microplastics

Fossils: Decline of crocodile ancestors was good news for early marine turtles

Italy: Fossil find reveals just how big carnivorous dinosaur may have grown

Palaeontology: Ice core evidence suggests famine worsened Black Death

Oceans: Debut of the global mix-master

Space Exploration: Mars' surface revealed in unprecedented detail

Breaking News: Accelerating the search for intelligent life in the universe

Breaking News: Saturn and Enceladus produce the same amount of plasma