The Great London [Search results for Genetics]

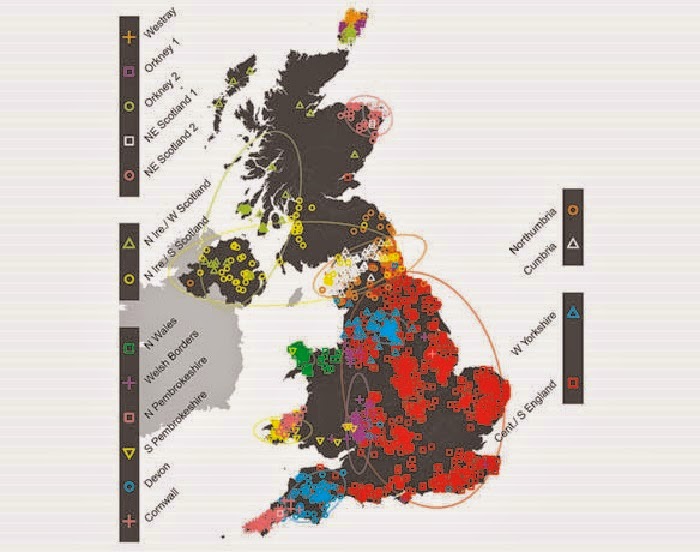

Genetics: First fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles

Genetics: A federal origin of Stone Age farming

Fossils: Mammal diversity exploded immediately after dinosaur extinction

Evolution: Sex cells evolved to pass on quality mitochondria

Breaking News: Natural selection, key to evolution, also can impede formation of new species

Fossils: Mammals evolved faster after dinosaur extinction

Early Humans: Modern humans out of Africa sooner than thought

Genetics: A 100-million-year partnership on the brink of extinction

Genetics: DNA analysis reveals Roman London was a multi-ethnic melting pot

Breaking News: Complex genetic ancestry of Americans uncovered

Scotland: Patrick Matthew: Evolution's overlooked third man

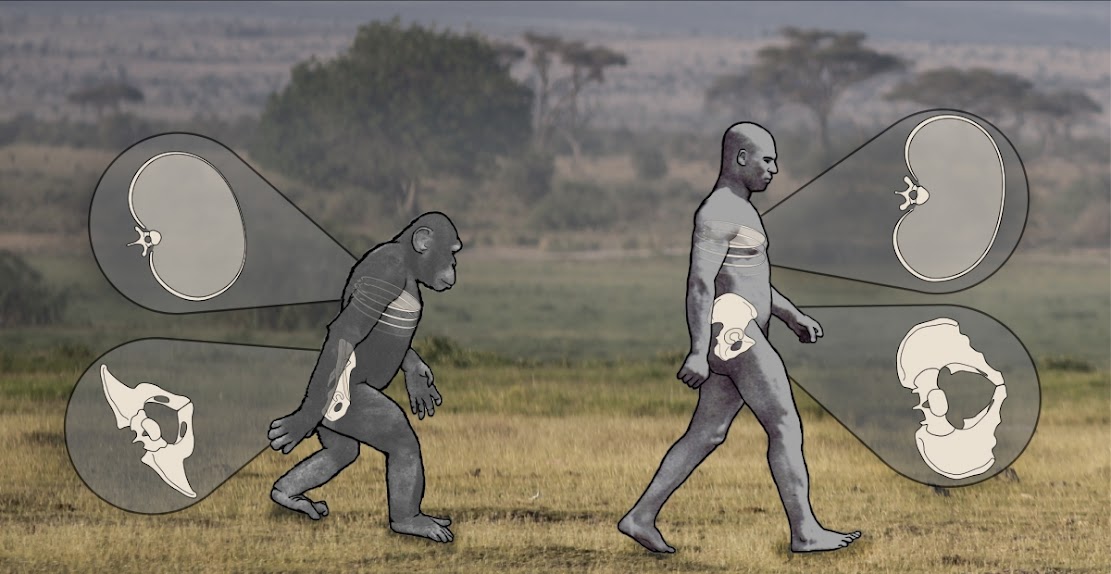

Genetics: Tweak in gene expression may have helped humans walk upright

Genetics: Mummies from Hungary reveal TB's Roman lineage

Genetics: Genes for nose shape found

Genetics: Scientists sequence ancient British 'gladiator' genomes from Roman York

Genetics: Scientists propose new evolution model for tropical rainforests

Genetics: Obesity in humans linked to fat gene in prehistoric apes