The Great London [Search results for Ireland]

UK: Human presence in Ireland pushed back by 2,500 years

Travel: 'Celts: Art and Identity' at the British Museum

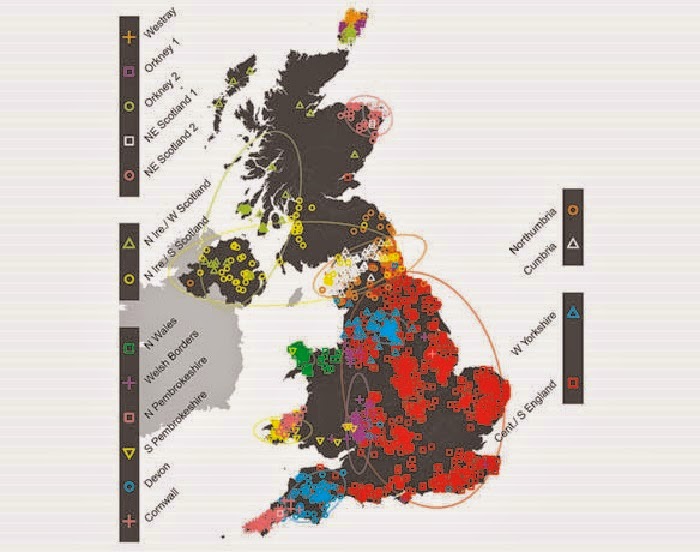

Genetics: First fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles

Travel: 'Beyond Caravaggio' at The National Gallery, London

UK: Ancient Britons' teeth reveal people were 'highly mobile' 4,000 years ago

UK: Mummification was common in Bronze Age Britain