The Great London [Search results for More Stuff]

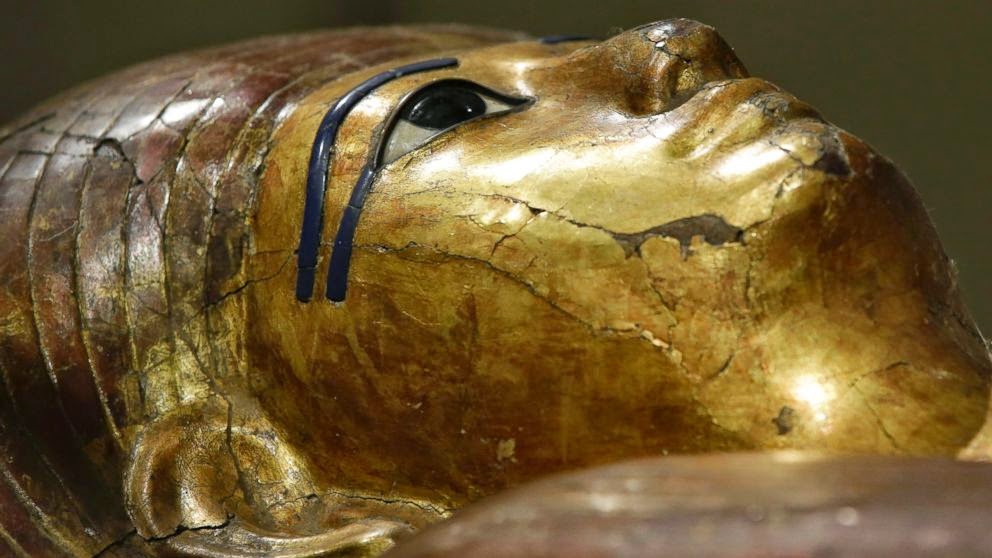

More Stuff: Turin Egyptian Museum gets overhaul of pharaonic proportions

United Kingdom: British pensioner 'finds' 2,300 year old ancient Greek gold crown in box under his bed

UK: Detectorist finds hoard of 5,000 Anglo-Saxon coins

More Stuff: 'Egyptian Magic' at the Museum of Civilization, Quebec

Cambodia: Lasers uncover hidden secrets of Cambodia's ancient cities

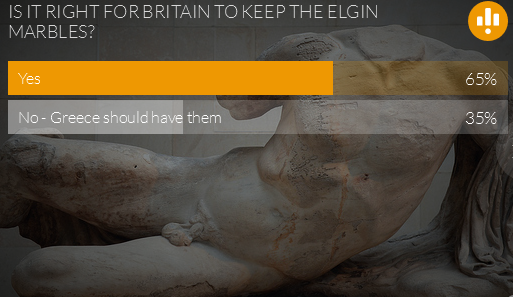

More Stuff: Is Greece about to lose the Parthenon Sculptures forever?

UK: 17th century plague pit unearthed in London

More Stuff: Telegraph: Greece has no legal claim to the Elgin Marbles

More Stuff: 'Papyri from Karanis: Voices from a multi-cultural society in ancient Fayum' at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo

More Stuff: 'A dream among splendid ruins...' at the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

More Stuff: 'Egypt: Millennia of Splendour' at the Museo Civico Archeologico in Bologna

More Stuff: Paris Egypt exhibit holds defiant message for Islamic State

UK: Handwriting analysis reveals unknown Magna Carta scribe