The Great London [Search results for Oceans]

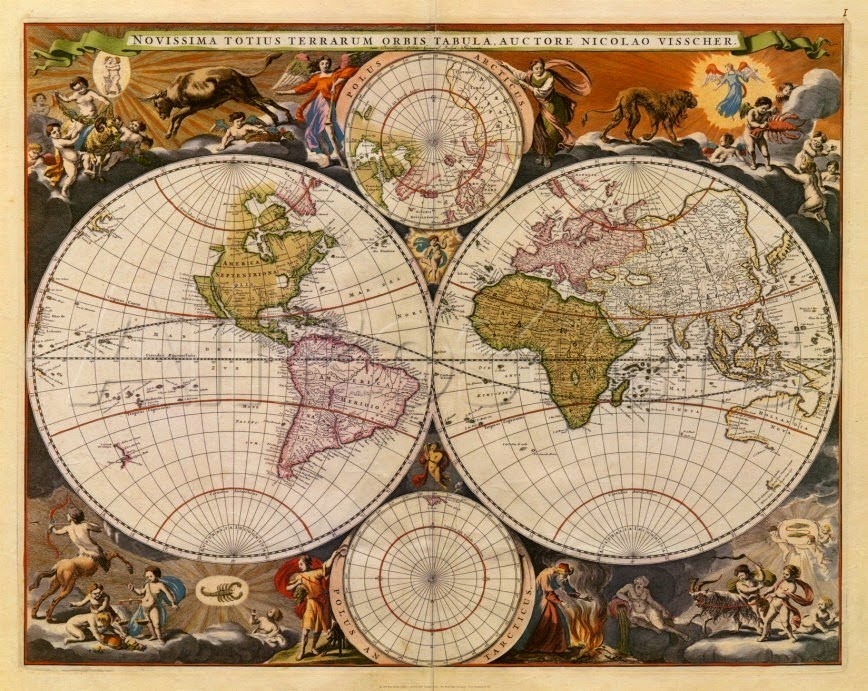

Oceans: Debut of the global mix-master

Astronomy: Strong ‘electric wind’ strips planets of oceans and atmospheres

Evolution: Life exploded on Earth after slow rise of oxygen

Geology: Copper gives an answer to the rise of oxygen

Oceans: Almost all seabirds to have plastic in gut by 2050

Namibia: Study provides strongest evidence oxygen levels were key to early animal evolution

Oceans: Rising carbon dioxide levels stunt sea shell growth

Palaeontology: Newly discovered pliosaur terrorised ancient Russian seas

Oceans: Heat release from stagnant deep sea helped end last Ice Age

Greenland: Greenland on thin ice?

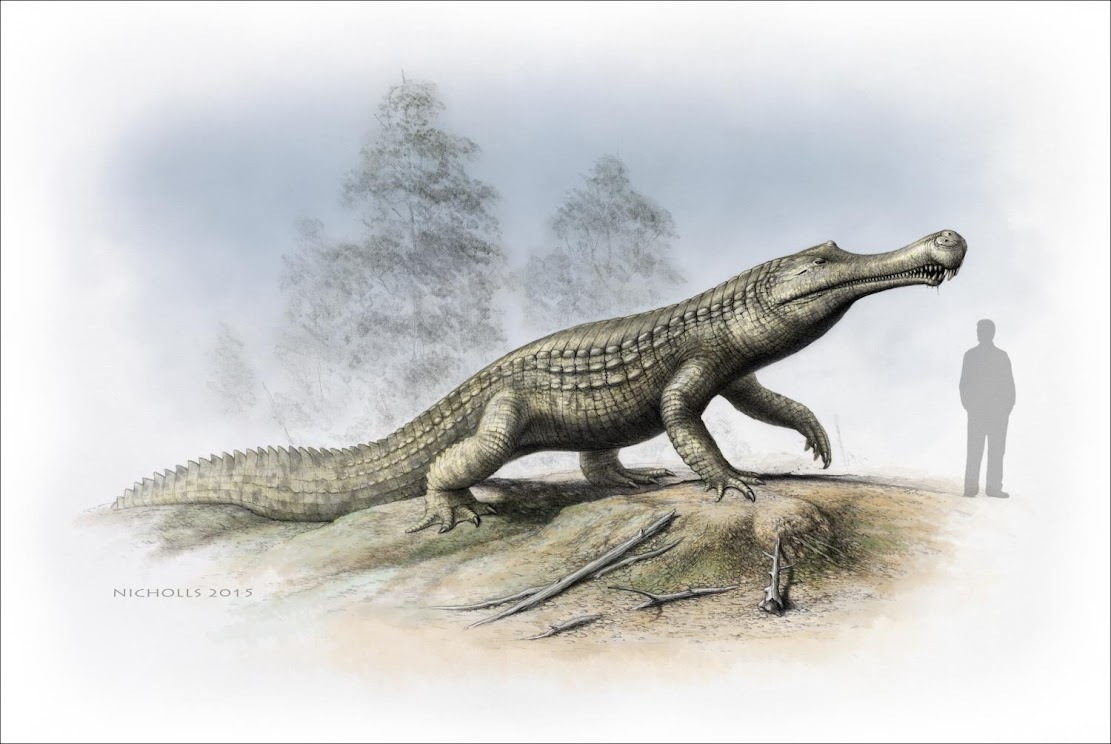

Fossils: Decline of crocodile ancestors was good news for early marine turtles

Environment: Warming opens famed Northwest Passage to navigation

Oceans: First evidence of deep-sea animals ingesting microplastics

Fossils: Cold snap: Climate cooling and sea-level changes caused crocodilian retreat

Oceans: Major shortfalls identified in marine conservation

Natural Heritage: Epoch-defining study pinpoints when humans came to dominate planet Earth

Oceans: Chemicals threaten Europe's killer whales with extinction