The Great London [Search results for Scotland]

Travel: 'Celts' at the National Museum of Scotland

Travel: 'Celts: Art and Identity' at the British Museum

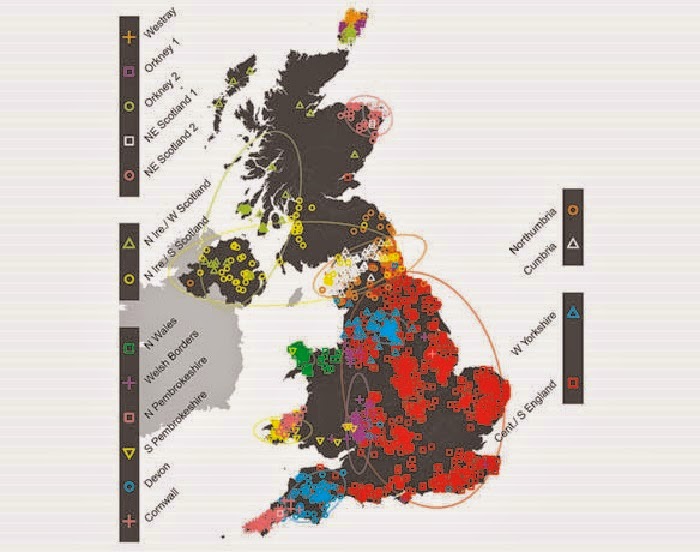

Genetics: First fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles

UK: Christie’s artefacts linked to organised crime

Scotland: 'Skeletons: Our Buried Bones' at the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow

Early Humans: Evidence of oat grinding by Stone Age hunter-gatherers found in Italy

UK: Remains of ‘father and son’ found in 2000 year old grave

UK: Britain's last hunter-gatherers discovered using breakthrough analysis of bone fragments

Palaeontology: Isle of Skye fossil makes three species one

Scotland: Patrick Matthew: Evolution's overlooked third man

Mauritius: Dodos might have been quite intelligent, new research finds

United Kingdom: Britain has kept the ‘Elgin Marbles’ for 200 years – now it's time to pass them on

UK: Human presence in Ireland pushed back by 2,500 years

Environment: Kew report urges global scientific community to secure health of the planet

Northern Europe: The coldest decade of the millennium?

Oceans: Chemicals threaten Europe's killer whales with extinction