The Great London [Search results for Space Exploration]

Breaking News: Solar storms trigger Jupiter's 'Northern Lights'

Space Exploration: Mars' surface revealed in unprecedented detail

Breaking News: Farthest galaxy detected

Archaeologists begin exploration of Shakespeare's Curtain Theatre

Space Exploration: Venus Express' swansong experiment sheds light on Venus' polar atmosphere

Space Exploration: Scientists identify mineral that destroys organic compounds, with implications for Mars Curiosity Mission

UK: British Museum to launch first major exhibition of underwater archaeology in May 2016

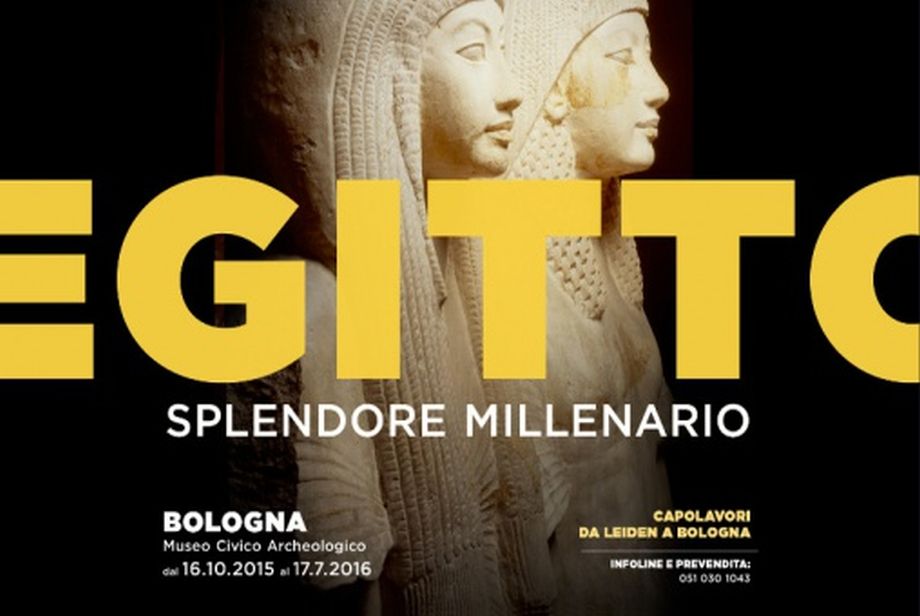

More Stuff: 'Egypt: Millennia of Splendour' at the Museo Civico Archeologico in Bologna