The Great London [Search results for design]

At the Heart of Popular Culture

The New Lighting Shop: Atrium

Great Legacy: Fossils and minerals take the antiques market by storm

UK: Roman fresco unearthed in London

UK: Roman gold ring depicting Cupid found in UK

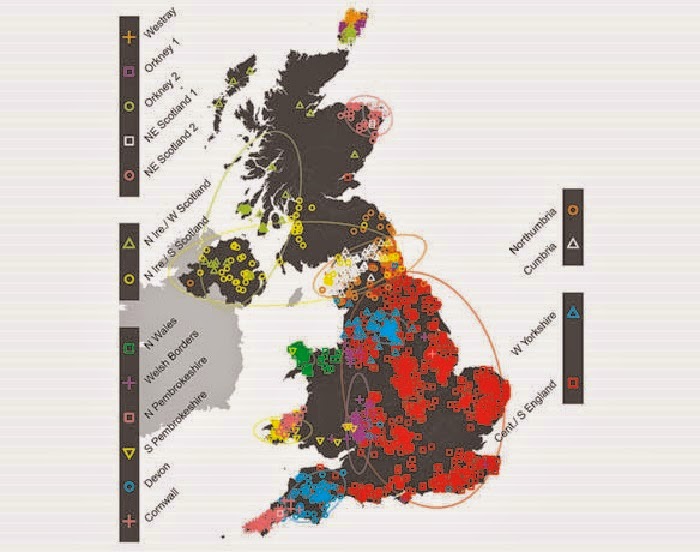

Genetics: First fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles

Unusual Female Stiletto

Travel: 'Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation' at the British Museum

UK: Norman castle remains found under Gloucester prison

Travel: 'Stonehenge: A Hidden Landscape' at MAMUZ Museum Mistelbach, Austria

Northern Europe: The last Viking and his 'magical' sword?

Travel: 'Celts: Art and Identity' at the British Museum