The Great London [Search results for history]

Palaeontology: Ice core evidence suggests famine worsened Black Death

Mauritius: Dodos might have been quite intelligent, new research finds

Nigeria: The British Museum distorts history and denies its racist past

Geology: Common magnetic mineral is reliable witness to Earth's history

Environment: Not so crowded house? New findings on global species richness

Travel: 'Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation' at the British Museum

Fossils: Ancient DNA traces extinct Caribbean 'Island Murderer' back to the dawn of mammals

Forensics: Palaeolithic remains show cannibalistic habits of human ancestors

Great Legacy: Fossils and minerals take the antiques market by storm

Genetics: A 100-million-year partnership on the brink of extinction

Fossils: Long-necked dino species discovered in Australia

Northern Europe: The last Viking and his 'magical' sword?

UK: DNA of bacteria responsible for London Great Plague of 1665 identified

UK: Archaeologists search for Roman remains in Gloucester

North America: Site with clues to fate of fabled Lost Colony may be saved

Greenland: Greenland on thin ice?

UK: Human presence in Ireland pushed back by 2,500 years

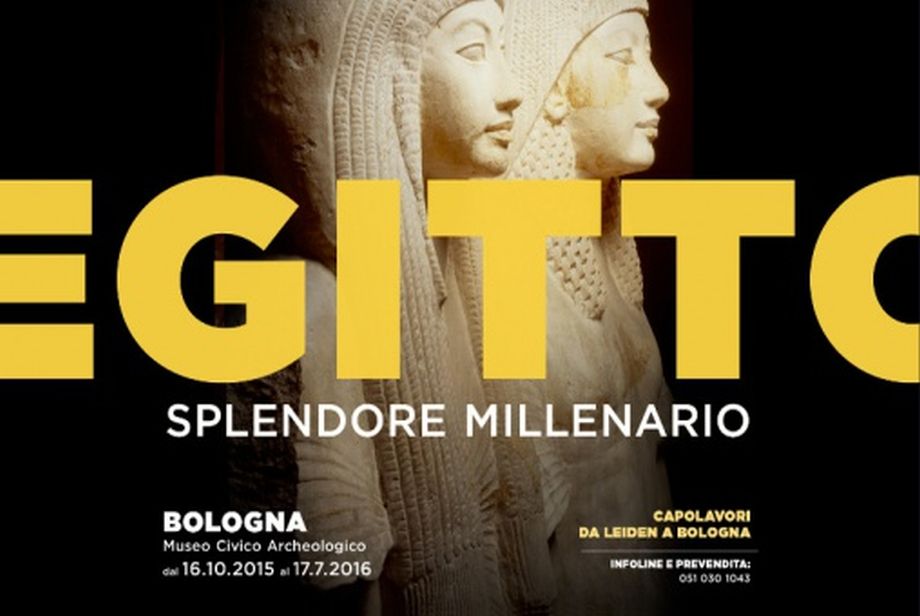

More Stuff: 'Egypt: Millennia of Splendour' at the Museo Civico Archeologico in Bologna

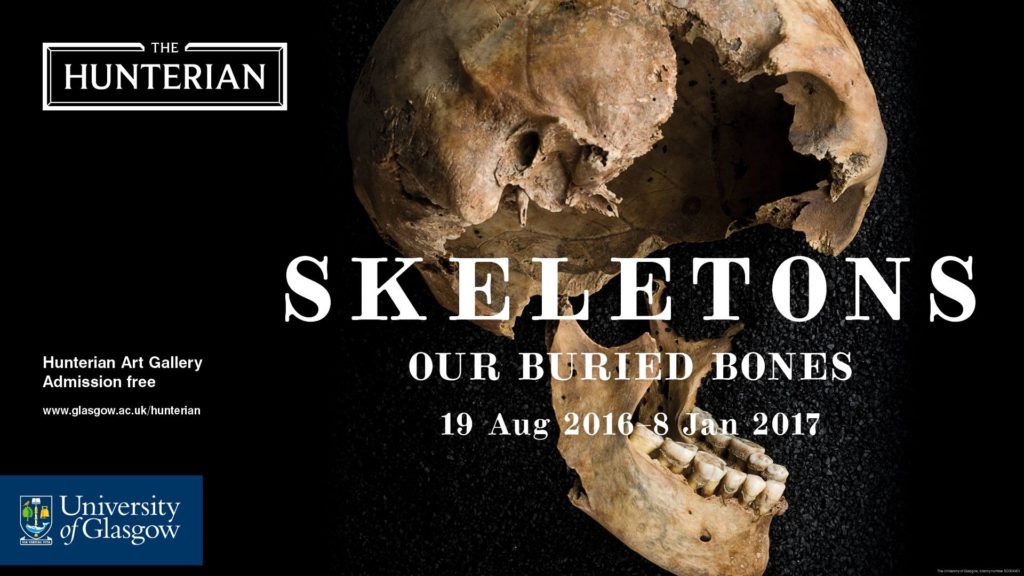

Scotland: 'Skeletons: Our Buried Bones' at the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow

Palaeontology: Africa’s earliest known coelacanth found in Eastern Cape