The Great London:

Scotland

Palaeontology: Isle of Skye fossil makes three species one

Travel: 'Celts' at the National Museum of Scotland

UK: Remains of ‘father and son’ found in 2000 year old grave

UK: 750-year-old skeletons will give picture of medieval Aberdeen

Scotland: Patrick Matthew: Evolution's overlooked third man

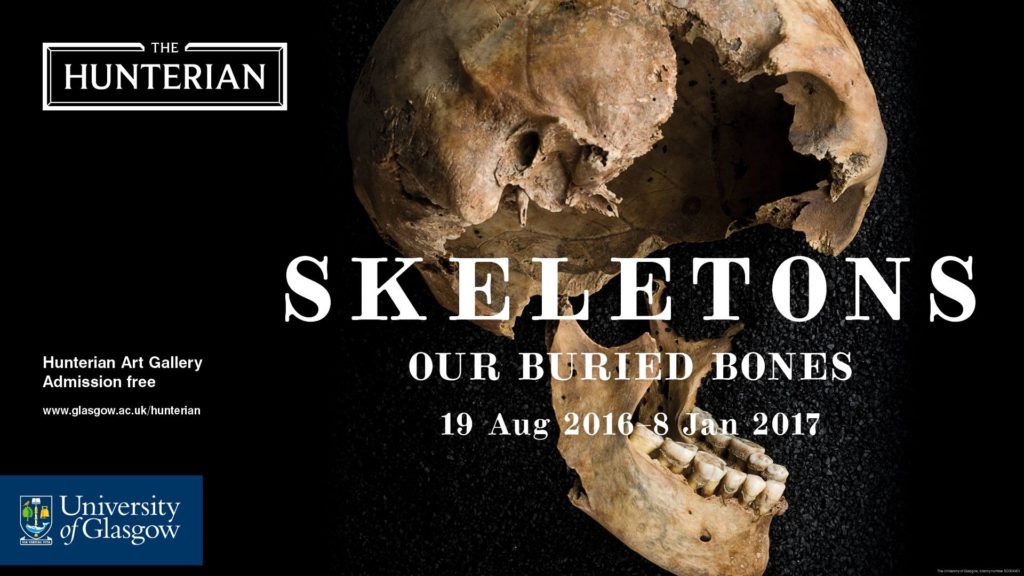

Scotland: 'Skeletons: Our Buried Bones' at the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow