The Great London [Search results for Universe]

Astrophysics: The Big Bang might have been just a Big Bounce

Astrophysics: Theory that challenges Einstein's physics could soon be put to the test

Astrophysics: Accelerating research into dark energy

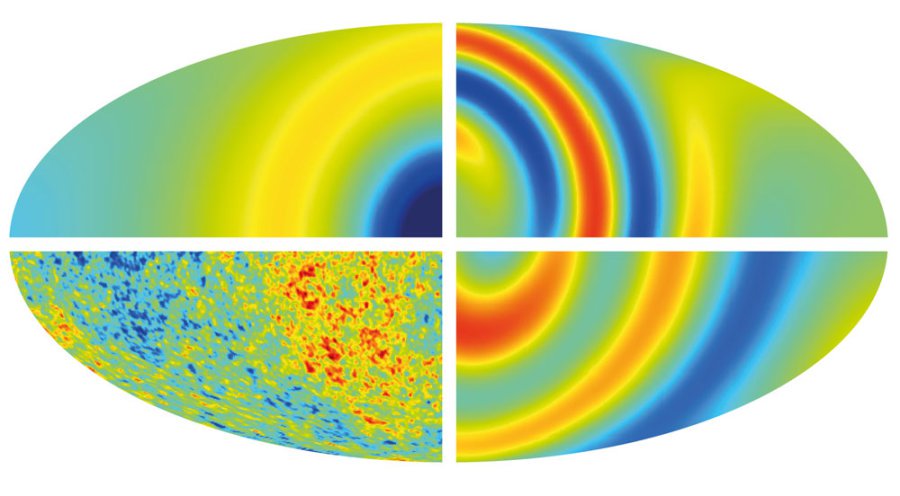

Astrophysics: Cosmology safe as universe has no sense of direction

Breaking News: Farthest galaxy detected

Breaking News: Unravelling the history of galaxies

Astronomy: Astronomers release spectacular survey of the distant Universe

Breaking News: Accelerating the search for intelligent life in the universe

Breaking News: New dwarf galaxies discovered in orbit around the Milky Way

More Stuff: 'Egyptian Magic' at the Museum of Civilization, Quebec

Astronomy: Proxima b is in host star's habitable zone, but could it really be habitable?

Scotland: Patrick Matthew: Evolution's overlooked third man

Grab Shell Dude: Going Vertical Review

Recommended Reading: 'Map of Life' predicts ET, so where is he?

Astronomy: Planet found in habitable zone around nearest star