The Great London [Search results for house]

UK: Remains of ‘father and son’ found in 2000 year old grave

Cambodia: Archaeologists digging in search of common people at Angkor Wat

More Stuff: 'Papyri from Karanis: Voices from a multi-cultural society in ancient Fayum' at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo

UK: Christie’s artefacts linked to organised crime

The London Oasis

Environment: Not so crowded house? New findings on global species richness

Dinosaurs: Scientists carry out 'autopsy' on life-sized T-Rex replica

Ecosystems: Humans artificially drive evolution of new species

Travel: 'Beyond Caravaggio' at The National Gallery, London

Great Legacy: Cyprus antiquity repatriated from United Kingdom

Great Legacy: First Chinese imperial firearm ever to appear at auction sells for US$2.5 million

Palaeontology: Isle of Skye fossil makes three species one

UK: Excavation of Roman Cemetery nominated for British archaeology award

India: Australian gallery identifies looted Indian treasures

United Kingdom: British MPs introduce Bill to return Parthenon Sculptures to Greece

UK: More than one in ten UK species threatened with extinction

Palaeontology: Ice core evidence suggests famine worsened Black Death

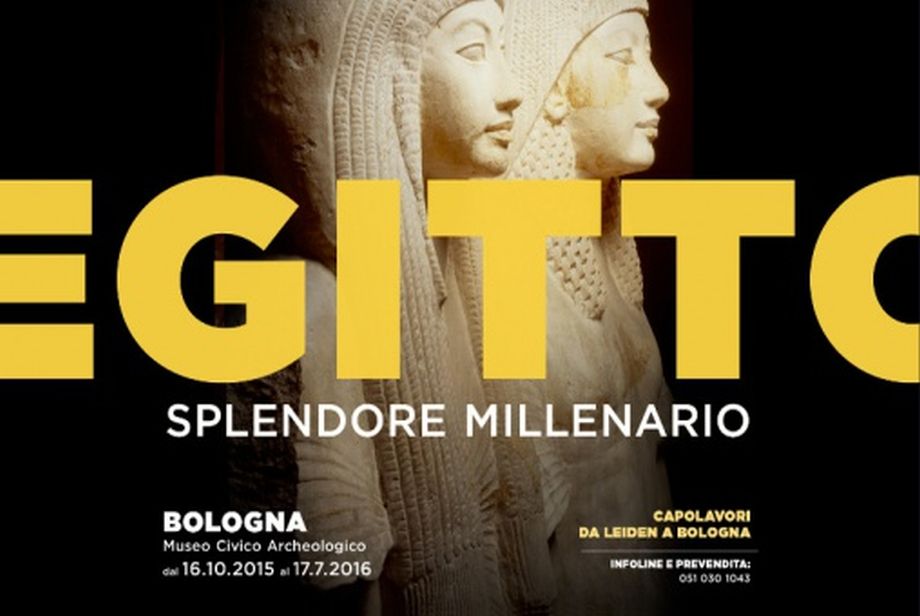

More Stuff: 'Egypt: Millennia of Splendour' at the Museo Civico Archeologico in Bologna

The London Architecture

Iraq: At Iraq's Nimrud, remnants of fabled city ISIS sought to destroy