The Great London [Search results for London]

Modern Townhouse in the Northern part of London

The 1st Cable Car in London

UK: Roman fort built in response to Boudicca’s revolt discovered in London

Modern Housing Complex in London

The London Architecture

UK: Roman fresco unearthed in London

UK: 2,000-year-old handwritten documents found in London mud

Forensics: New research to shed fresh light on the impact of industrialisation

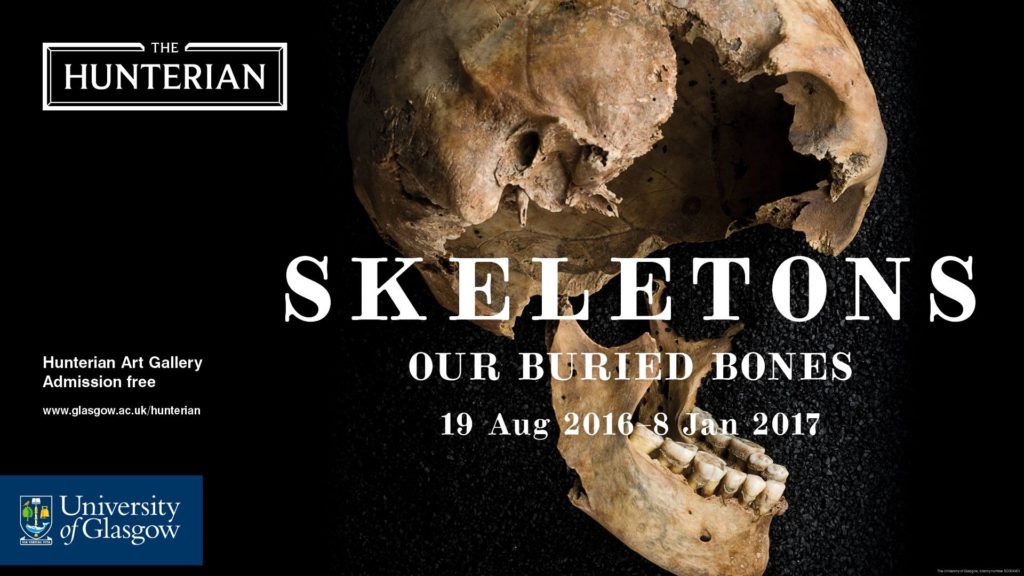

Scotland: 'Skeletons: Our Buried Bones' at the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow

UK: Dig at theatre where Shakespeare worked uncovers a surprise

UK: DNA of bacteria responsible for London Great Plague of 1665 identified

Underwater Archaeology: 17th century gun-carriage salvaged from London wreck

Basketball Arena for the London Olympic Games

UK: 17th century plague pit unearthed in London

Genetics: DNA analysis reveals Roman London was a multi-ethnic melting pot

UK: Evidence of early Christian presence in Roman London

UK: Thousands of skeletons removed from Bedlam

UK: Replicas of Palmyra arch to go on show in London, NY

The London Oasis

Syria's Palmyra arch recreated in London